Early Blight of Potato

(PP1892, Reviewed Nov. 2025)Early blight is caused by the fungal pathogen Alternaria solani. The disease affects leaves, stems, and tubers, and can reduce tuber yield and size. Reductions in tuber quality due to early blight compromise storage longevity and marketability of fresh-market and processing crops.

Andrew P. Robinson, Professor and Extension Potato Agronomist, 线上赌博app/University of Minnesota

Julie S. Pasche, Professor and Neil C. Gudmestad Endowed Chair of Potato Pathology, Department of Plant Pathology, 线上赌博app

Early blight is widely distributed within the U.S. and occurs annually to some degree in most potato production regions. In the Midwest, foliar infection by the pathogen is the most damaging phase, whereas tuber infection may be more costly in the western U.S. Early blight severity is dependent upon foliar wetness from rain, dew or irrigation; plant nutritional status and cultivar susceptibility.

The disease first develops on physiologically mature and senescing foliage; therefore, early maturing cultivars are most susceptible. Although potato is the primary host, A. solani also infects other solanaceous crops, including tomato, eggplant and hairy nightshade.

Symptoms

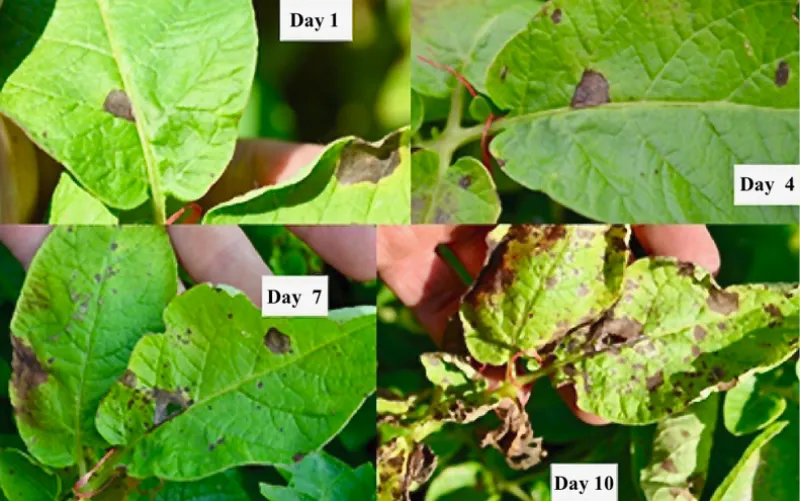

Early blight foliar lesions can be diagnosed in the field by the characteristic dark concentric rings alternating with bands of light-tan tissue, giving them a distinctive target spot appearance (Figure 1a). Initial symptoms of early blight appear as small, circular or irregular dark brown to black spots, typically starting on the older (lower) leaves (Figure 1b). These spots enlarge up to 3/8 inch in diameter and gradually may become angular in shape, often restricted by leaf veins as they expand.

Initial early blight lesions may be confused with brown spot (caused by small-spore Alternaria species) (Figure 2a) or black dot (caused by Colletotrichum coccodes) lesions (Figure 2b). However, brown spot and black dot lesions do not develop dark concentric rings characteristic of early blight infection. Brown spot lesions rarely become larger than 3-4mm and are typically round. First early blight lesions appear about two to three days after infection, with sporulation at the lesion margin occurring three to five days later.

Multiple lesions on the same leaf may coalesce, or grow together, to form what appears to be one large lesion (Figure 3a), potentially resembling grey mold caused by Botrytis cinerea (Figure 3b). Chlorosis (yellowing of plant tissue) may be visible around clusters of infections by the early blight pathogen (Figure 3a). Elongated, brown to black lesions may develop on the stems and petioles of infected plants (Figure 4).

Later in the growing season, as infections become more severe, lower leaves may drop, and numerous lesions may appear on the upper leaves (Figure 5).

Premature leaf senescence, reduced yield and low tuber dry matter content are likely when plants suffer from severe foliar infection during the tuber bulking stage.

Early blight tuber symptoms appear as dark and sunken lesions on the surface (Figure 6). Tuber lesions may be circular or irregular in shape and surrounded by a raised dark brown border (Figure 7).

The underlying tuber tissue is dry and dark brown with a corky texture (Figure 8). Tuber symptoms of early blight may manifest only after months of storage (Figure 9) and can be confused with Fusarium dry rot (Figure 10).

Disease Cycle

A. solani inoculum for primary infections of potato foliage most commonly originates from spores (conidia) on plant debris from previous seasons, typically in neighboring fields. Other less common sources of pathogen inoculum include infected seed tubers, volunteer potatoes or alternative hosts such as tomatoes and hairy nightshade. Overwintering spores that serve as the initial inoculum move within and between fields carried by air currents, windblown soil and plant debris, splashing rain and irrigation water. Spores can survive freezing temperatures on or just below the soil surface.

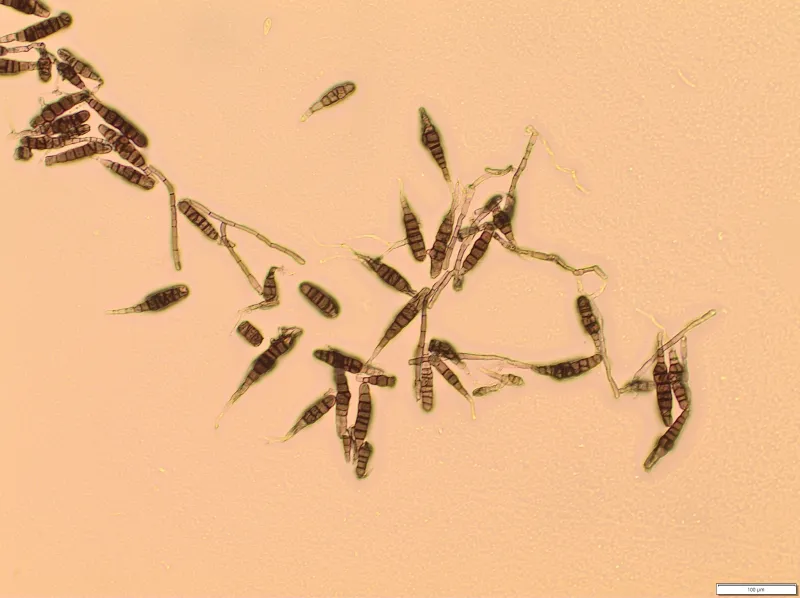

A. solani spores formed on infected foliage are dislodged during conducive environmental conditions (Figure 11). Alternating wet and dry periods are most favorable for spore formation, dispersal and the spread of the fungus to healthy tissue. Multiple sporulation and infection cycles occur within a single season, leading to an exponential increase in foliar disease as the growing season progresses. The infection rate is generally low in the early season, and increases after flowering and is most rapid during tuber bulking (Figure 12).

The optimum temperature for spore germination and infection by A. solani is 68 to 86 F, although it can occur between 41 and 95 F. Sporulation and disease development occur between 50 and 95 F, with the optimum temperature of 72 to 81 F. Because of the favorable wet/dry cycle, peak spore dissemination occurs during midmorning and declines throughout the afternoon into night.

High humidity or free moisture and favorable temperatures are required for spore germination and penetration into susceptible plants. Penetration can occur directly through host epidermal cells or via natural openings like stomata or wounds. The pathogen favors older, senescing leaf tissue. Plants stressed by injury, nutrient deficiency and insect feeding are highly vulnerable to infection.

During harvest, tubers often come into contact with A. solani spores that have accumulated on the soil surface during the growing season or were dislodged from desiccated vines. Spores germinate and penetrate tubers through lenticels and wounds caused by mechanical injury (Figure 13).

Tuber infection is most common in potato cultivars highly susceptible to skinning, such as red- and white-skinned cultivars. Infection does not spread during storage and, unlike late blight tuber lesions, early blight tuber lesions typically do not serve as infection courts for other decay organisms.

Early Blight Management

- Rotate fields to nonhost crops for at least three years (three to four-year crop rotation).

- Select a late-season cultivar. Resistance is associated with plant maturity, and early maturing cultivars are generally more susceptible.

- Time irrigation to minimize leaf wetness duration during cloudy weather, and allow sufficient time for leaves to dry prior to nightfall.

- Avoid nitrogen and phosphorus deficiency.

- Eradicate weed hosts such as hairy nightshade to reduce inoculum for future potato crops.

- Scout fields regularly for infection beginning after plants reach 12 inches in height. Pay particular attention to field edges adjacent to fields where potatoes were grown the previous year.

- Monitor physiological days (P-Days) with the North Dakota Agricultural Weather Network (NDAWN) Potato Blight app.

- Kill vines two to three weeks before harvest to allow for adequate skin set.

- Avoid injury and skinning during harvest.

- Store tubers under conditions that promote wound healing (fresh air, 95% to 99% relative humidity and temperatures of 55 to 60 F) for two to three weeks after harvest. Following wound healing, store tubers in a dark, dry and well-ventilated location, gradually cooled to a temperature appropriate for the desired market.

Fungicides for Management

- Most commercially acceptable potato cultivars are susceptible to early blight; therefore, foliar fungicide application is the primary means for managing early blight.

- Fungicide selection and rotation should be approached with the goals of obtaining effective disease management and reducing the risk of the early blight pathogen developing fungicide insensitivity.

- Practice good resistance management strategies by 1) rotating and combining (tank-mix or prepackaged) fungicides with differing modes of action and 2) including multisite (group M) fungicides.

- Mancozeb and chlorothalonil are the most frequently used protectant (multisite; group M) fungicides for early blight management but provide insufficient disease reductions under high disease pressure.

- The application of systemic fungicides with a single site-specific mode of action is often necessary during periods of high early blight pressure.

- Fungicides with the same single-site mode of action (FRAC group) should not be applied consecutively.

- Discontinue the application of boscalid (Endura®) for early blight due to lack of efficacy.

- Refer to the most current “North Dakota Field Crop Plant Disease Management Guide” (PP622) for updated information on products, modes of action and application rates.

Fungicide Resistance in Alternaria solani

In a 2020-21 survey conducted by North Dakota State University, the F129L mutation associated with insensitivity to several fungicides in the Quinone outside Inhibiting (QoI; FRAC group 11) class was detected in 97% of 213 A. solani isolates collected throughout the U.S. and Canada (Shrestha et al. unpublished) (Table 1).

Table 1. Sensitivity and mutation profile of four single-site mode of action fungicide groups labeled for the early blight management of potatoes.

Fungicide Group | Active Ingredient1 | FRAC2 Code | Fungicide Sensitivity/Mutation Profile |

Quinone outside Inhibitor (QoI) | Azoxystrobin | 11 | n Insensitivity to QoI fungicides conveyed by the F129L mutation is widespread across every potato-growing region in the US (Bauske et al. 2018a; Pasche et al. 2005; Shrestha et al. unpublished). n Cross-insensitivity is expected among these products. n Field efficacy of QoI-insensitive isolates is comparable to common protectant fungicides chlorothalonil and mancozeb. |

Anilino-Pyrimidine (AP) | Pyrimethanil | 9 | n Insensitivity to the AP fungicide pyrimethanil has been reported at low frequency in several states, including Minnesota (Fonseka and Gudmestad 2016). n Field efficacy of these products remains strong. |

Demethylation inhibitors (DMI) | Difenoconazole | 3 | n Insensitivity to the DMI fungicides difenoconazole and metconazole has been observed; however, limiting use has been demonstrated to be an effective resistance management strategy (Fonseka and Gudmestad 2016). n Cross-insensitivity has been observed. n Field efficacy of these products remains strong. |

Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor (SDHI) | Boscalid | 7 | n Insensitivity to SDHI fungicides conveyed by at least nine mutations is widespread across the US and Canada (Mallik et al. 2014; Bauske et al. 2018a; Shrestha et al. 2024). n Cross-insensitivity has been observed in some studies. n Slight reductions in field efficacy have been observed; however, fluopyram and pydiflumetofen continue to be critical for effective early blight management. n Boscalid use is no longer recommended for early blight management due to insensitivity. |

1 Not a comprehensive list, includes only those chemistries with insensitivity data.

2 FRAC = Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (www.frac.info)

Insensitivity to Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibiting (SDHI; FRAC group 7) fungicides has also become problematic in recent years. Nine Sdh gene mutations conferring insensitivity to SDHI fungicides have been characterized by 线上赌博app (Mallik et al. 2014; Shrestha et al. 2024). Among 216 A. solani isolates collected in 2020-21, 81% contained one of the nine Sdh gene mutations (Shrestha et al. unpublished). The co-occurrence of two mutations within a single isolate was detected in 2% of isolates. Reduction in the sensitivity to SDHI fungicides fluopyram and pydiflumetofen has been observed in the laboratory and greenhouse (Shrestha et al. 2024).

Insensitivity to anilino-pyrimidine (AP; FRAC group 9) fungicide has been reported in several states, including Minnesota (Fonseka and Gudmestad, 2016). Insensitivity to the Demethylation inhibitor (DMI; FRAC 3) fungicides difenoconazole and metconazole has been observed; however, limiting use has been demonstrated to be an effective resistance management strategy (Fonseka and Gudmestad 2016). Sensitivity to AP and DMI fungicide classes has not been evaluated in over a decade.

Selected References

Bauske, M.J., Mallik, I., Yellareddygari, S.K.R., and Gudmestad, N.C. 2018(a). Spatial and temporal distribution of mutations conferring QoI and SDHI resistance in Alternaria solani across the United States. Plant Dis. 102:349-358.

Fonseka, D.L., and Gudmestad, N.C. 2016. Spatial and temporal sensitivity of Alternaria species associated with potato foliar diseases to demethylation inhibiting and anilino-pyrimidine fungicides. Plant Dis. 100:1848-1857.

Fungicide Resistance Action Committee, FRAC Code List© 2024. Fungal control agents sorted by cross-resistance pattern and mode of action (including coding for FRAC Groups on product labels). Online publication.

Mallik, I., Arabiat, S., Pasche, J.S., Bolton, M.D., Patel, J.S., and Gudmestad, N.C. 2014. Molecular characterization and detection of mutations associated with resistance to succinate dehydrogenase- inhibiting fungicides in Alternaria solani. Phytopathology 104:40-49.

Pasche, J.S., Piche, L.M., and Gudmestad, N.C. 2005. Effect of the F129L mutation in Alternaria solani on fungicides affecting mitochondrial respiration. Plant Dis. 89:269-278.

Shrestha, S., Mallik, I., Gudmestad, N. C., and Pasche, J. S. 2024. Detection of novel Sdh gene mutations in Alternaria solani conferring reduced sensitivity to SDHI fungicides (Abstr.) Phytopathology 114: S1.60. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-114-11-S1.1